Arno Brandlhuber in Conversation with Muck Petzet and Florian Heilmeyer

Muck Petzet: Together we’ve visited the Antivilla in Krampnitz, on which you’re currently working. How would you describe the two buildings located there, which you want to retain as part of this project?

Arno Brandlhuber: They’re two very unpretentious buildings that housed a state-owned knitwear factory in GDR times. One of them was built in the late 1950s and the other was built by a group of building apprentices around 1980. To begin with, they are not particularly attractive buildings. Especially the building from the 1980s, which will become the Antivilla, is exceptionally ugly—it’s an overgrown single-family house, a monstrosity with almost no remarkable features. But on closer inspection some remarkable idiosyncrasies become evident, like the unnecessarily large number of small windows that were built; they’re all the same size, but made with different techniques: lintel, arch, and so on. It was the trainees who did the building.

MP: Why are you retaining these ugly buildings?

AB: First of all, it’s simply cheaper to use what is already there than to build something new. The anticipated demolition costs for both buildings had actually already been deducted from the price of the real estate. Conserving them has, as it were, paid off for us threefold: we saved the costs of demolition, the property was nevertheless cheaper, and we?no longer had the necessity to erect a new building. Secondly, and to us this was at least as important, there was a chance here to have significantly more useable floor area, since the area of the two existing buildings is much greater than what we would have been permitted to rebuild after demolishing them. The building code would have permitted three small new buildings with a total of only 250 square meters. By contrast, the buildings that already exist there have 250 square meters per floor. So by retaining the existing buildings, we got approximately 750 square meters of additional floor area. Thirdly, there was also an emotional factor. That the two buildings had survived over the years with their obvious visual shortcomings, and that despite everything they had not been torn down long ago—that had honestly touched me. They are survivors. Demolition would have meant all that emotional energy would have been lost along with the total embodied energy of production.

Florian Heilmeyer: Which of the arguments you mentioned was the decisive one? Asked hypothetically: if it had been possible to construct the same amount of space in new buildings of exactly the same size and shape, would you have preserved both buildings anyway?

AB: Yes, we definitely would have worked with what already existed. Forty percent of the costs of a new building go into the shell and core work. So it’s pointless to tear down something that could just as well continue to serve as the basis for something else. Of course it’s necessary to carefully examine what can still be done with the existing building. That’s an interesting reversal of the question: suddenly it’s less about what I want, and more about what the building can achieve.

FH: So what abilities did the existing building have in this case?

AB: In Krampnitz we have a building with tiny or missing windows, load-bearing interior walls, and a corrugated-fiber cement roof contaminated with asbestos. That raises certain questions in relation to adaptive reuse.

FH: Sounds like good reasons for demolition. So what are you doing?

AB: The roof is being disposed of and we’re replacing it with a slightly sloped concrete slab that has several functions: we’re using waterproof concrete, so it functions as a roof membrane without any additional roofing. Beyond that it’s suitable for walking on, so it serves as additional space. In addition, as the slab independently spans between the exterior walls, the load-bearing interior walls become superfluous and an open floor plan is possible. We also no longer need all of the exterior walls for structural support, so we’re able to remove two thirds of them. We’ll get jackhammers and invite friends to a demolition party. Where do we want holes in the walls? Where do we want to look out? Toward the woods or the lake? Clear it out! The rough holes that result will be sealed afterward from within with glass panels. And voilà—the Antivilla is finished. One single move—the new roof slab—makes it all possible.

MP: And the other building?

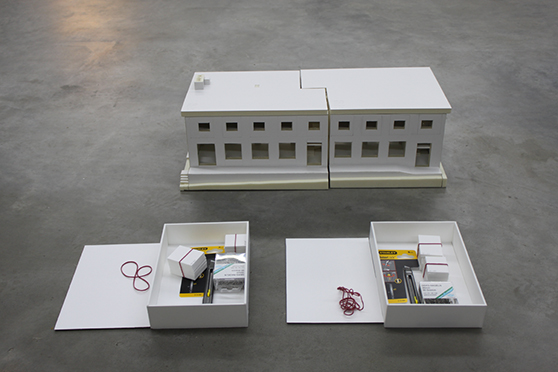

AB: That has a lot more going for it. A well-functioning roof, columns instead of load-bearing walls, and large windows at the ground floor, but also here there are tiny windows on the upper floor, and just one single staircase. All the needed features exist. But they aren’t always in the right place. So we developed a strategy of direct self-empowerment. We asked the two future users to move these features: the large windows from the ground floor can be copied to the upper floor, and the existing stairs can be shifted. These stipulations raise interesting questions: where do you need a staircase, and where a large window? Would the small existing window be sufficient in this location? All the changes are “copy and paste” within the existing buildings—the existing elements are the kit of parts; nothing new may be added.

FH: That sounds as if the two ugly buildings are ultimately being retained not only because it makes economical and spatial sense, but also because it would be fun.

AB: There’s actually something else, too, which I think is essential. The question of excess: it’s a typical situation for small weekend cottages. For weekend use, seventy square meters is more than enough. Our project work creates two buildings that are a total of 430 square meters too large. That raises questions about the follow-up costs, especially for insulation and heating. With the Antivilla, we reply by establishing different indoor climate zones. We don’t heat the entire building evenly; there’s a hot core, the sauna, as a central heat source. Then there’s a warm zone: bathroom, shower, kitchen, and other areas with flexible climate requirements. We create these with curtains. Like an onion they surround the core; with the curtains, the zones can be adjusted and readjusted, again and again. And we don’t need any thermal insulation: during the summer everything can be used without difficulty, in the spring and fall almost everything, and in the winter, you need to settle for a smaller area. In the remaining area, you need to wear a thick sweater. Incidentally, we stay within the legal requirements, we simply construe them differently: we don’t upgrade the building; instead we reduce the area in winter, defining different heat and use zones.

FH: What do you do with the space that you don’t need?

AB: We don’t know that yet. That’s precisely what’s so fascinating— the excess space opens ups new questions about use and accessibility. By retaining the existing, a “plus” emerges, one that otherwise would never have been considered for financial reasons. Suddenly, an indeterminate generosity emerges: we have too much space. Who wants to use it? For what? It’s a by-product that has arisen only from retaining and working with the existing space as a resource, and it costs nothing.

FH: A “luxury of the void.” That suits Brandenburg very well.

AB: Ordinarily something like this doesn’t happen with architecture as it never produces “too much”; everything is precisely calculated. In this case, however, we came upon a completely different economic model: the added value doesn’t emerge by creating something new, but as a result of doing less. Instead of investing in more thermal insulation, we invest in more room.

MP: With these indoor climate zones, you question established notions of standards. You don’t create a fully insulated house in which all the rooms have the same climatic conditions. Instead, you actually create extreme differences. The residents then have to find out when they need what.

AB: Yes. Why should everything always be equipped with the same standards? There are enormous costs associated with this and, as a consequence, a need to refinance through continuous use and specifying functions. Why can’t we just say, no, for different uses and different users there are naturally different standards, and these can exist well side by side?

MP: Do you think that would also be transferable to a different scale? Aren’t we dealing here with a very specific individual case for a very specific clientele? To begin with, in this case you yourself are the client, and it’s also easy to imagine that other artists, architects, and designers would have fun with such a concept . . .

AB: Of course, it’s ideal when projects demonstrate new options in an exemplary way. I hope very much that from time to time we create examples that are transferable. Our projects think about the relationships between living and working in new ways; we call into question building standards that are rarely challenged. A building like the one on Brunnenstrasse—as we quickly realized—could be built twenty times over in Berlin and there would still be enough interested buyers.

FH: On Brunnenstrasse you also challenged the standards that one would expect to see in a new building. You can do a maximum amount, but leave it largely undefined and unfinished. Unlike in Krampnitz, however, Brunnenstrasse is largely a new building only using the ruins of the existing cellar. So to what extent are the two related projects?

AB: In both cases the place and the existing condition prescribe certain bonds. Generally speaking, I like the notion that ideas already exist in one place. There’s so much information in what already exists that there’s really never any reason to develop entirely new forms. You simply need to discover the information and synthesize its complexity. In Brunnenstrasse it was initially very tangible information, namely the remains of the basement of a house that was left uncompleted after an investor went bankrupt in 1994. Similar to the situation in Krampnitz, the property was somewhat cheaper because of the ostensibly unusable, abandoned construction site; the costs for its demolition were already deducted. And we didn’t tear it down, but continued what existed instead.

FH: Not building within what exists, but upon.

AB: You could say that. Architecture is always “within a context” anyway, and there’s a surrounding environment that “exists” and defines certain bonds. The purchase of the Brunnenstrasse site was tied to the condition, among other things, that the rear building had to receive sunlight down to the first floor. That resulted in the slope of our roof. Those are compulsory bonds. There are also voluntary bonds, such as the floor-to-floor height and the cornice height. We could have defined these freely, but we decided to orient ourselves on the neighboring buildings. The story heights of the two neighboring buildings are different, and connecting them resulted in offsets within our floor slabs and the roof edge. You could say that’s nonsense, we don’t need that. Or you deal with the consequences arising from it. In this case, the differences in height provided the opportunity to organize the floors without prescribing too much to the users. In addition, the result is a kind of folded structure, which is effective in bracing the house and carries the external staircase in the courtyard. When we take the constraints seriously and think through the consequences, productive strategies for the design can emerge.

FH: You’re using the term “bonds,” which was also used by Oswald Mathias Ungers.

AB: Yes, but I want to expand the term beyond the formal consequences that were the essential aspect for Ungers and his students. Let’s stay with the Brunnenstrasse example: beyond the formal and legal conditions that we had to meet, there were other bonds. We wanted to move into the building together with the gallerists from KOW, who are friends of ours, and the magazine 032c. These aren’t tenants who can ensure maximum profits, so we had to offer rents that are relatively low for this area. We reversed the usual economic model and first established the rental price. From that, we derived how much the building could cost at most. Many decisions became easier, also for future users: how much floor area do you want? How much will that cost with burnished concrete floors? How much with parquet flooring? With lower ceiling heights, we could take on another tenant—how much could we save by doing that? We discussed all of that quite openly with the tenants. Interesting discussions arose about what’s really needed and wanted. Many then prefer more floor area or space with a more basic, robust, and well-usable fit-out standard. Then it was easy to decide to use lots of inexpensive polycarbonate for the façade, especially since it scatters the light, producing a very good quality of light for studio or office use. And the exposed concrete doesn’t have a Tadao And?? quality. If we had provided the “normal residential standard” here, we could have only built a much smaller area with our budget. It’s about revealing what is possible beyond the usual standards. It’s about offering options that can be appropriated and are neutral with respect to use, ones that also meet future changing conditions.

MP: What fascinates you about such bonds? You say it helps when you have constraints. What’s wrong with a tabula rasa?

AB: There’s nothing wrong with a tabula rasa. But: it doesn’t exist. Everywhere there’s something already there. What’s more, in Germany the population is steadily declining. Except for some inner city areas, we can hardly afford to continue spending money for new buildings! It’s already all there. We actually have too many. From an overall economic perspective, it’s completely senseless to keep constructing new buildings. Of course there are situations that are not suitable for reuse, ones that really have no positive qualities whatsoever. Demolition should not be forbidden. But it could be sensible to evaluate certain buildings or typologies to determine whether they are generally useful as models for certain forms of reuse. What could churches become? What about gas stations? The result could be a very inspiring guide.

FH: If, as you say, solutions beyond the prevailing building standards would be interesting for many of these cases of adaptive reuse, why aren’t these standards conceived to be much more liberal or at least discussed more, especially in a city like Berlin, which still has a large reservoir of derelict sites and unused buildings and spaces?

AB: There’s simply no interest in building cheaply—especially not in urban areas that are easy to market. The users who would be dependent upon it don’t yet express themselves effectively enough. Why should the private sector do it? High-priced products are much more lucrative for everyone involved in selling or creating them: developers, investors, real estate brokers, and, of course, architects as well. For architects, it’s even less attractive, because searching for solutions beyond the standards results in more work and, as long as our fees are based on the construction costs, lower fees. Moreover, there’s also a certain bias in the public debate, because the established stakeholders often present any questioning of the standards as meaning that something would be taken away from the underprivileged. This knee-jerk reaction of discrediting the standards question doesn’t bring us any further if we sincerely want to try to offer affordable living space in inner city areas, whether as rental apartments or as owner-occupied condominiums.

MP: That’s right. We must have the courage to seek solutions beyond the standards. Otherwise the whole field will be determined only by industrial solutions.

AB: But as architects, we then quickly start operating in an area that’s not consistent with the “state of the art.” Such experiments can lead to dramatic additional costs . . .

MP: . . . or to court. The mere fact that a solution doesn’t comply with the standards is sufficient to compel the architect to rectify deficiencies.

AB: Exactly. That’s naturally a negative aspect of our strategy. In Brunnenstrasse and for the Antivilla in Krampnitz, we are our own clients after all, so we could venture into a complex process and then wait to see what solutions the analysis of the bonds led us to. But normally a builder wants to know right at the beginning of the project how it will appear in the end. Our strategy is also of little value for competitions. We can’t depict a simulated final state. We can only suggest analyzing the site and the surroundings during the entire planning and construction period, and to develop rigorously consistent decisions along the way.

FH: By and large, architects are still trained in college to build something new. Shouldn’t we also start there and give much more significance to this concept of continued building?

AB: I think it makes sense that students first learn to come to terms with themselves and a defined area of space. That’s a big step and is simply more fun. I, too, avoided all the seminars where the subject was building services, construction law, or adaptive reuse. They simply weren’t particularly attractive.

MP: The topic simply isn’t sexy.

AB: But that only holds true for simulated projects in college. In the real world, rebuilding becomes sexy. Then there’s a specific situation, a relationship, an exciting building. Then it’s immediately exciting. Construction law is nothing exciting in the first place. Not until it becomes a tool that you can work with, then it’s productive and exciting.

MP: That brings us to the profession’s self-image, which sees itself as a master builder and less as a master rebuilder.

AB: The image of the architect has been heavily influenced—at least in the last ten or twenty years—by images of iconic architecture, almost exclusively of new buildings, and especially parametric design and its promises. It has meanwhile been proven that this formal parameterization is a dead end. Because it’s simply not capable of factoring in complex bonds—social, cultural, and political ties. Thus it leads only to iconic architecture: highly complex in formal terms, but as architecture, ultimately of low complexity because so much is not taken into consideration. In this respect, the finance crisis comes at just the right moment for architecture, since it forces us to deal with our resources more economically.

MP: Does that lead us to a new, more prudent attitude in terms of what exists?

AB: Today’s architects cannot, in any case, simply present ingenious sketches that are meant to resolve everything, whether it’s with a thick pencil or an automated computer process. They have to deal instead with much more complex existing situations. Architecture can then also be a partial solution or a temporary improvement. It’s no longer about permanent solutions or the eternal setting. I find the loss of this architectural aspiration toward permanence to be a great relief.

The Standards

Arno Brandlhuber in Conversation with Muck Petzet and Florian Heilmeyer

Muck Petzet: Together we’ve visited the Antivilla in Krampnitz, on which you’re currently working. How would you describe the two buildings located there, which you want to retain as part of this project?

Arno Brandlhuber: They’re two very unpretentious buildings that housed a state-owned knitwear factory in GDR times. One of them was built in the late 1950s and the other was built by a group of building apprentices around 1980. To begin with, they are not particularly attractive buildings. Especially the building from the 1980s, which will become the Antivilla, is exceptionally ugly—it’s an overgrown single-family house, a monstrosity with almost no remarkable features. But on closer inspection some remarkable idiosyncrasies become evident, like the unnecessarily large number of small windows that were built; they’re all the same size, but made with different techniques: lintel, arch, and so on. It was the trainees who did the building.

MP: Why are you retaining these ugly buildings?

AB: First of all, it’s simply cheaper to use what is already there than to build something new. The anticipated demolition costs for both buildings had actually already been deducted from the price of the real estate. Conserving them has, as it were, paid off for us threefold: we saved the costs of demolition, the property was nevertheless cheaper, and we

no longer had the necessity to erect a new building. Secondly, and to us this was at least as important, there was a chance here to have significantly more useable floor area, since the area of the two existing buildings is much greater than what we would have been permitted to rebuild after demolishing them. The building code would have permitted three small new buildings with a total of only 250 square meters. By contrast, the buildings that already exist there have 250 square meters per floor. So by retaining the existing buildings, we got approximately 750 square meters of additional floor area. Thirdly, there was also an emotional factor. That the two buildings had survived over the years with their obvious visual shortcomings, and that despite everything they had not been torn down long ago—that had honestly touched me. They are survivors. Demolition would have meant all that emotional energy would have been lost along with the total embodied energy of production.

Florian Heilmeyer: Which of the arguments you mentioned was the decisive one? Asked hypothetically: if it had been possible to construct the same amount of space in new buildings of exactly the same size and shape, would you have preserved both buildings anyway?

AB: Yes, we definitely would have worked with what already existed. Forty percent of the costs of a new building go into the shell and core work. So it’s pointless to tear down something that could just as well continue to serve as the basis for something else. Of course it’s necessary to carefully examine what can still be done with the existing building. That’s an interesting reversal of the question: suddenly it’s less about what I want, and more about what the building can achieve.

FH: So what abilities did the existing building have in this case?

AB: In Krampnitz we have a building with tiny or missing windows, load-bearing interior walls, and a corrugated-fiber cement roof contaminated with asbestos. That raises certain questions in relation to adaptive reuse.

FH: Sounds like good reasons for demolition. So what are you doing?

AB: The roof is being disposed of and we’re replacing it with a slightly sloped concrete slab that has several functions: we’re using waterproof concrete, so it functions as a roof membrane without any additional roofing. Beyond that it’s suitable for walking on, so it serves as additional space. In addition, as the slab independently spans between the exterior walls, the load-bearing interior walls become superfluous and an open floor plan is possible. We also no longer need all of the exterior walls for structural support, so we’re able to remove two thirds of them. We’ll get jackhammers and invite friends to a demolition party. Where do we want holes in the walls? Where do we want to look out? Toward the woods or the lake? Clear it out! The rough holes that result will be sealed afterward from within with glass panels. And voilà—the Antivilla is finished. One single move—the new roof slab—makes it all possible.

MP: And the other building?

AB: That has a lot more going for it. A well-functioning roof, columns instead of load-bearing walls, and large windows at the ground floor, but also here there are tiny windows on the upper floor, and just one single staircase. All the needed features exist. But they aren’t always in the right place. So we developed a strategy of direct self-empowerment. We asked the two future users to move these features: the large windows from the ground floor can be copied to the upper floor, and the existing stairs can be shifted. These stipulations raise interesting questions: where do you need a staircase, and where a large window? Would the small existing window be sufficient in this location? All the changes are “copy and paste” within the existing buildings—the existing elements are the kit of parts; nothing new may be added.

FH: That sounds as if the two ugly buildings are ultimately being retained not only because it makes economical and spatial sense, but also because it would be fun.

AB: There’s actually something else, too, which I think is essential. The question of excess: it’s a typical situation for small weekend cottages. For weekend use, seventy square meters is more than enough. Our project work creates two buildings that are a total of 430 square meters too large. That raises questions about the follow-up costs, especially for insulation and heating. With the Antivilla, we reply by establishing different indoor climate zones. We don’t heat the entire building evenly; there’s a hot core, the sauna, as a central heat source. Then there’s a warm zone: bathroom, shower, kitchen, and other areas with flexible climate requirements. We create these with curtains. Like an onion they surround the core; with the curtains, the zones can be adjusted and readjusted, again and again. And we don’t need any thermal insulation: during the summer everything can be used without difficulty, in the spring and fall almost everything, and in the winter, you need to settle for a smaller area. In the remaining area, you need to wear a thick sweater. Incidentally, we stay within the legal requirements, we simply construe them differently: we don’t upgrade the building; instead we reduce the area in winter, defining different heat and use zones.

FH: What do you do with the space that you don’t need?

AB: We don’t know that yet. That’s precisely what’s so fascinating— the excess space opens ups new questions about use and accessibility. By retaining the existing, a “plus” emerges, one that otherwise would never have been considered for financial reasons. Suddenly, an indeterminate generosity emerges: we have too much space. Who wants to use it? For what? It’s a by-product that has arisen only from retaining and working with the existing space as a resource, and it costs nothing.

FH: A “luxury of the void.” That suits Brandenburg very well.

AB: Ordinarily something like this doesn’t happen with architecture as it never produces “too much”; everything is precisely calculated. In this case, however, we came upon a completely different economic model: the added value doesn’t emerge by creating something new, but as a result of doing less. Instead of investing in more thermal insulation, we invest in more room.

MP: With these indoor climate zones, you question established notions of standards. You don’t create a fully insulated house in which all the rooms have the same climatic conditions. Instead, you actually create extreme differences. The residents then have to find out when they need what.

AB: Yes. Why should everything always be equipped with the same standards? There are enormous costs associated with this and, as a consequence, a need to refinance through continuous use and specifying functions. Why can’t we just say, no, for different uses and different users there are naturally different standards, and these can exist well side by side?

MP: Do you think that would also be transferable to a different scale? Aren’t we dealing here with a very specific individual case for a very specific clientele? To begin with, in this case you yourself are the client, and it’s also easy to imagine that other artists, architects, and designers would have fun with such a concept . . .

AB: Of course, it’s ideal when projects demonstrate new options in an exemplary way. I hope very much that from time to time we create examples that are transferable. Our projects think about the relationships between living and working in new ways; we call into question building standards that are rarely challenged. A building like the one on Brunnenstrasse—as we quickly realized—could be built twenty times over in Berlin and there would still be enough interested buyers.

FH: On Brunnenstrasse you also challenged the standards that one would expect to see in a new building. You can do a maximum amount, but leave it largely undefined and unfinished. Unlike in Krampnitz, however, Brunnenstrasse is largely a new building only using the ruins of the existing cellar. So to what extent are the two related projects?

AB: In both cases the place and the existing condition prescribe certain bonds. Generally speaking, I like the notion that ideas already exist in one place. There’s so much information in what already exists that there’s really never any reason to develop entirely new forms. You simply need to discover the information and synthesize its complexity. In Brunnenstrasse it was initially very tangible information, namely the remains of the basement of a house that was left uncompleted after an investor went bankrupt in 1994. Similar to the situation in Krampnitz, the property was somewhat cheaper because of the ostensibly unusable, abandoned construction site; the costs for its demolition were already deducted. And we didn’t tear it down, but continued what existed instead.

FH: Not building within what exists, but upon.

AB: You could say that. Architecture is always “within a context” anyway, and there’s a surrounding environment that “exists” and defines certain bonds. The purchase of the Brunnenstrasse site was tied to the condition, among other things, that the rear building had to receive sunlight down to the first floor. That resulted in the slope of our roof. Those are compulsory bonds. There are also voluntary bonds, such as the floor-to-floor height and the cornice height. We could have defined these freely, but we decided to orient ourselves on the neighboring buildings. The story heights of the two neighboring buildings are different, and connecting them resulted in offsets within our floor slabs and the roof edge. You could say that’s nonsense, we don’t need that. Or you deal with the consequences arising from it. In this case, the differences in height provided the opportunity to organize the floors without prescribing too much to the users. In addition, the result is a kind of folded structure, which is effective in bracing the house and carries the external staircase in the courtyard. When we take the constraints seriously and think through the consequences, productive strategies for the design can emerge.

FH: You’re using the term “bonds,” which was also used by Oswald Mathias Ungers.

AB: Yes, but I want to expand the term beyond the formal consequences that were the essential aspect for Ungers and his students. Let’s stay with the Brunnenstrasse example: beyond the formal and legal conditions that we had to meet, there were other bonds. We wanted to move into the building together with the gallerists from KOW, who are friends of ours, and the magazine 032c. These aren’t tenants who can ensure maximum profits, so we had to offer rents that are relatively low for this area. We reversed the usual economic model and first established the rental price. From that, we derived how much the building could cost at most. Many decisions became easier, also for future users: how much floor area do you want? How much will that cost with burnished concrete floors? How much with parquet flooring? With lower ceiling heights, we could take on another tenant—how much could we save by doing that? We discussed all of that quite openly with the tenants. Interesting discussions arose about what’s really needed and wanted. Many then prefer more floor area or space with a more basic, robust, and well-usable fit-out standard. Then it was easy to decide to use lots of inexpensive polycarbonate for the façade, especially since it scatters the light, producing a very good quality of light for studio or office use. And the exposed concrete doesn’t have a Tadao Andō quality. If we had provided the “normal residential standard” here, we could have only built a much smaller area with our budget. It’s about revealing what is possible beyond the usual standards. It’s about offering options that can be appropriated and are neutral with respect to use, ones that also meet future changing conditions.

MP: What fascinates you about such bonds? You say it helps when you have constraints. What’s wrong with a tabula rasa?

AB: There’s nothing wrong with a tabula rasa. But: it doesn’t exist. Everywhere there’s something already there. What’s more, in Germany the population is steadily declining. Except for some inner city areas, we can hardly afford to continue spending money for new buildings! It’s already all there. We actually have too many. From an overall economic perspective, it’s completely senseless to keep constructing new buildings. Of course there are situations that are not suitable for reuse, ones that really have no positive qualities whatsoever. Demolition should not be forbidden. But it could be sensible to evaluate certain buildings or typologies to determine whether they are generally useful as models for certain forms of reuse. What could churches become? What about gas stations? The result could be a very inspiring guide.

FH: If, as you say, solutions beyond the prevailing building standards would be interesting for many of these cases of adaptive reuse, why aren’t these standards conceived to be much more liberal or at least discussed more, especially in a city like Berlin, which still has a large reservoir of derelict sites and unused buildings and spaces?

AB: There’s simply no interest in building cheaply—especially not in urban areas that are easy to market. The users who would be dependent upon it don’t yet express themselves effectively enough. Why should the private sector do it? High-priced products are much more lucrative for everyone involved in selling or creating them: developers, investors, real estate brokers, and, of course, architects as well. For architects, it’s even less attractive, because searching for solutions beyond the standards results in more work and, as long as our fees are based on the construction costs, lower fees. Moreover, there’s also a certain bias in the public debate, because the established stakeholders often present any questioning of the standards as meaning that something would be taken away from the underprivileged. This knee-jerk reaction of discrediting the standards question doesn’t bring us any further if we sincerely want to try to offer affordable living space in inner city areas, whether as rental apartments or as owner-occupied condominiums.

MP: That’s right. We must have the courage to seek solutions beyond the standards. Otherwise the whole field will be determined only by industrial solutions.

AB: But as architects, we then quickly start operating in an area that’s not consistent with the “state of the art.” Such experiments can lead to dramatic additional costs . . .

MP: . . . or to court. The mere fact that a solution doesn’t comply with the standards is sufficient to compel the architect to rectify deficiencies.

AB: Exactly. That’s naturally a negative aspect of our strategy. In Brunnenstrasse and for the Antivilla in Krampnitz, we are our own clients after all, so we could venture into a complex process and then wait to see what solutions the analysis of the bonds led us to. But normally a builder wants to know right at the beginning of the project how it will appear in the end. Our strategy is also of little value for competitions. We can’t depict a simulated final state. We can only suggest analyzing the site and the surroundings during the entire planning and construction period, and to develop rigorously consistent decisions along the way.

FH: By and large, architects are still trained in college to build something new. Shouldn’t we also start there and give much more significance to this concept of continued building?

AB: I think it makes sense that students first learn to come to terms with themselves and a defined area of space. That’s a big step and is simply more fun. I, too, avoided all the seminars where the subject was building services, construction law, or adaptive reuse. They simply weren’t particularly attractive.

MP: The topic simply isn’t sexy.

AB: But that only holds true for simulated projects in college. In the real world, rebuilding becomes sexy. Then there’s a specific situation, a relationship, an exciting building. Then it’s immediately exciting. Construction law is nothing exciting in the first place. Not until it becomes a tool that you can work with, then it’s productive and exciting.

MP: That brings us to the profession’s self-image, which sees itself as a master builder and less as a master rebuilder.

AB: The image of the architect has been heavily influenced—at least in the last ten or twenty years—by images of iconic architecture, almost exclusively of new buildings, and especially parametric design and its promises. It has meanwhile been proven that this formal parameterization is a dead end. Because it’s simply not capable of factoring in complex bonds—social, cultural, and political ties. Thus it leads only to iconic architecture: highly complex in formal terms, but as architecture, ultimately of low complexity because so much is not taken into consideration. In this respect, the finance crisis comes at just the right moment for architecture, since it forces us to deal with our resources more economically.

MP: Does that lead us to a new, more prudent attitude in terms of what exists?

AB: Today’s architects cannot, in any case, simply present ingenious sketches that are meant to resolve everything, whether it’s with a thick pencil or an automated computer process. They have to deal instead with much more complex existing situations. Architecture can then also be a partial solution or a temporary improvement. It’s no longer about permanent solutions or the eternal setting. I find the loss of this architectural aspiration toward permanence to be a great relief.